When we talk about lessons learned, today’s health care reform efforts are often held up to the measuring stick of President Bill Clinton’s failed health reform proposal in 1993.

When we talk about lessons learned, today’s health care reform efforts are often held up to the measuring stick of President Bill Clinton’s failed health reform proposal in 1993.

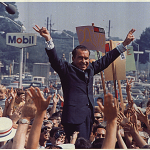

But an earlier national reform experience—President Richard Nixon’s attempts to pass a comprehensive health insurance plan in 1971 and again in 1974—provide an equally important cautionary tale as we reform supporters look at Majority Leader Reid’s bill today, with all its imperfections, and look at getting from here to the Rose Garden.

In 1971, Nixon came before Congress proposed a national health strategy that would have required all employers to provide employees coverage with minimum benefit standards, created subsidies for low- and middle-income families, established caps on cost-sharing for families, built state exchanges or pools for those ineligible for Medicaid or employer plans, and instituted cost containment measures. But Democrats rejected Nixon’s proposal. It wasn’t universal health care, they said, and what we needed was universal health care. By '74, the common wisdom was that Watergate would sweep Nixon out of office, and the country would elect a Democratic president who would shepherd in Real Health Reform.

It’s been 35 years since Nixon proposed his Comprehensive Health Insurance Plan. Then, health care costs were just over 7 percent of the Gross Domestic Product; today, they account for over 16 percent. In 1974, there were 25 million uninsured Americans Nixon sought to cover. Estimates suggest there are almost twice that many today.

While not perfect, Nixon's bill is one that most any Congressional supporter of reform would call a big victory if passed today. But it didn’t, in part because of opposition from progressives. And that opposition, so vocal then, can be heard again in today’s debate, saying this isn’t universal health care, and what we need is universal health care. And until we get that, we’ll just wait. “I would rather see us do nothing now,” former New England Journal of Medicine editor Marcia Angell wrote after the House bill came out, “and have a better chance of trying again later and then doing it right.”

But commentators like Ezra Klein have pointed out that things tend not to go like that. With each generation that passes on health reform, the vision gets smaller, and the political hurdles bigger.

“For a growing number of Americans, the cost of care is becoming prohibitive. And even those who can afford most care may find themselves impoverished by a catastrophic medical expenditure...Things do not have to be this way. We can change these conditions--indeed, we must change them if we are to fulfill our promise as a nation. Good health care should be readily available to all of our citizens.”

That was Nixon, in 1971. His words and his health reform proposal came in the wake of the Great Society, when it was still widely accepted that government was on the side of the people. It’s hard to imagine anyone in Republican leadership making such a promise today. With the exception of Sen. Snowe, those who lead the GOP today seem to deny, as dogma, a constructive role for government in the lives of ordinary people.

History should be corrective agent enough to show that scrapping the possible in favor of some more ideal plan at some future time is not the moral ground—it’s the opposite. Waiting means leaving millions of people at risk; people who are right now uninsured, who are unprotected by inadequate plans, or who are desperately holding onto employer coverage they risk losing in the worst jobs economy in generations.

History (and the ghost of Nixon’s health reform proposal) asks that we stay at the table and make these bills as good as possible. But sometimes we need to remind each other of history, and how close it still is, and what is asking us to do.

--Kate Petersen, Health Policy Hub blogger

Photo credit: Wikimedia commons