photo credit: Big Stock

Unaffordable health care continues to be a problem for individuals and families in the United States, with two-thirds of patients reporting concern over their ability to pay for medical expenses in 2021. These unaffordable health care costs often become medical debt, especially for those who are uninsured or underinsured and those living in low-income communities and communities of color. Nationally, 23 percent of working-age adults have medical debt, and the number rises to 31 percent for Black people due to unfair and discriminatory barriers to health care. Medical debt not only impedes individuals’ ability to pay for basic necessities, it also has a lasting impact on both financial and physical health by ruining credit ratings and causing people to postpone getting the health care they need.

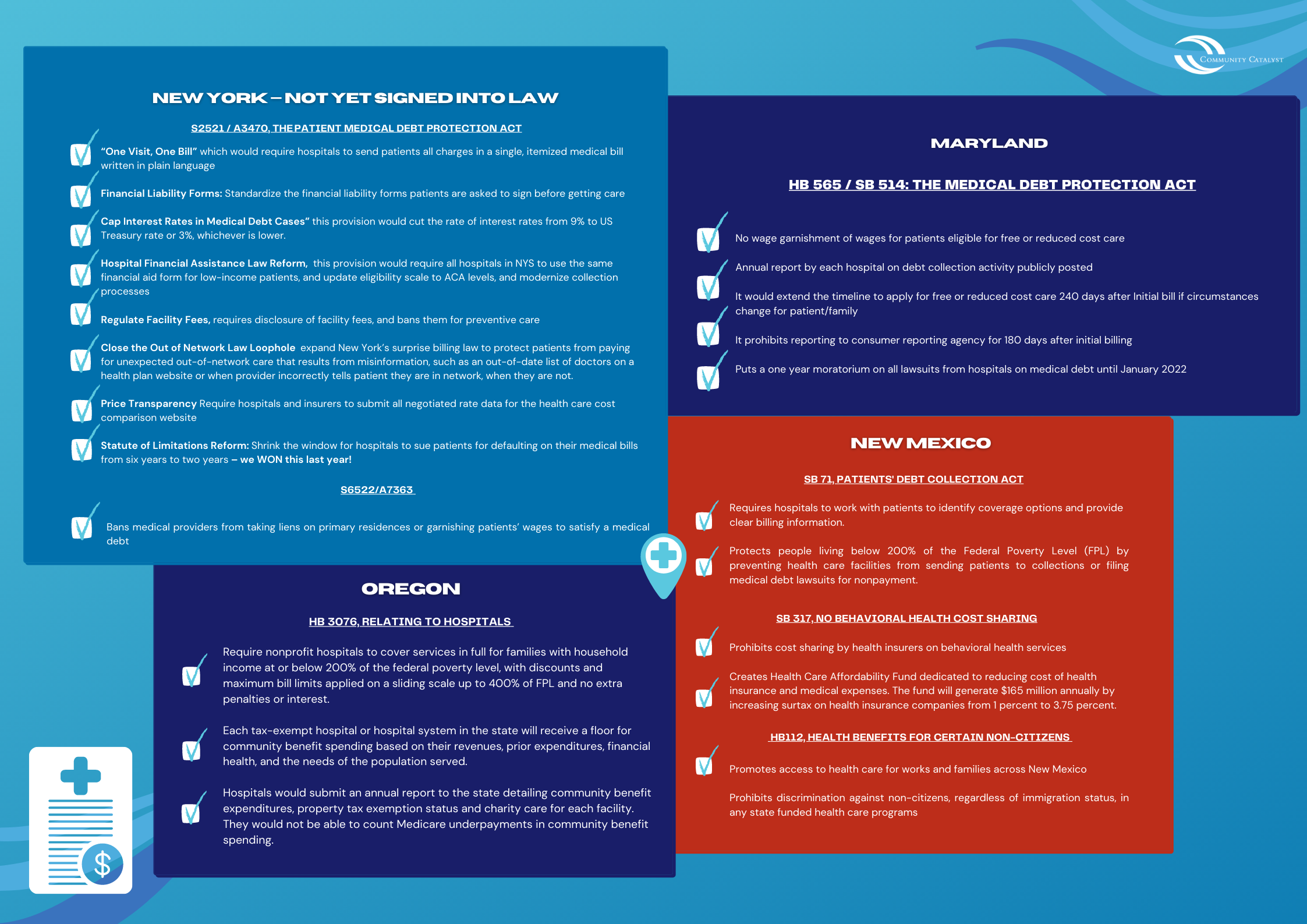

To address this problem, several states have put forward legislation to protect patients from medical debt through improving hospital financial assistance policies and restricting debt collection activities against low-income individuals. In a June panel discussion hosted by Community Catalyst’s Community Benefit and Economic Stability Project, advocates from four states – Maryland, New Mexico, New York, and Oregon – shared their successful strategies for advancing community-driven policies that address economic and health inequities and effectively reduce medical debt.

Each of these states enacted legislation with unique provisions, though advocates utilized similar strategies to succeed in their efforts, including:

1. Combining data and personal stories for effective messaging

Advocates across all four states emphasized the importance of data for backing up key protections included in their legislation, while also highlighting stories from individuals burdened by medical debt. This ensured their arguments were always grounded in the experiences of community members.

In New York, advocates used data from the Urban Institute to highlight racial disparities in medical debt. In Albany County, where more than 60 percent of residents are people of color, people are two and one-half times more likely to have medical debt in collections than in counties with predominantly white populations. Advocates also utilized the public court database to identify over 53,000 lawsuits issued by hospitals in the last five years, 5,000 of which were brought during the pandemic. This led to influential media coverage in the New York Times. Similarly, advocates in Maryland released a research report with data on the number of medical debt lawsuits and wage garnishments filed by non-profit Maryland hospitals, as well as a statewide poll showing widespread, bipartisan support for the protections included in a legislative proposal.

Combining statistics with stories proved to be a successful strategy for the state advocates. The Community Service Society of New York helped launch We The Patients, a digital platform that gives community members a voice to share their experiences in the health care system. Advocates in New Mexico and Maryland used their strong community base to identify people willing to take action and share their stories on the detrimental impact of medical debt. Interestingly, more legislators were informed directly by these individuals since they were more accessible during the pandemic due to virtual legislative sessions. In Oregon, advocates specifically identified hospital employees being sued by their own employer, which served as particularly compelling stories.

2. Building a powerful coalition and using grassroots organizing to engage community

A broad coalition of diverse community organizations able to engage in grassroots organizing was another powerful advocacy strategy. Advocates in Maryland formed the End Medical Debt Maryland coalition made up of 58 organizations representing 400,000 Marylanders. They also used their networks of local community organizations to engage and mobilize historically excluded populations including the Latino immigrant community. New Mexico advocates put together a coalition of groups with legal advocacy expertise, grassroots organizing experience, as well as clinical providers. They engaged individuals and families on issues related to health and economic inequities, with a particular focus on building power in communities of color. Through Casa de Salud, they also mobilized more than 60 health care workers to share stories illustrating the long-term impact of medical debt on patients’ ability to afford basic necessities and access care.

3. Developing a targeted strategy to address the opposition

In all four states, advocates faced opposition from hospital associations, which argued that hospitals had adequate policies in place to protect low-income patients from medical debt and that restricting debt collection activities would negatively affect hospitals’ financial health. To refute these arguments, advocates in Maryland worked together with health economists at Boston University to do a research study estimating that a prohibition on lawsuits under $1,000 would cause an insignificant revenue loss per hospital of about $7,000 per year. This amount is negligible to hospitals but would prevent roughly 7,000 lawsuits per year, making a huge difference for low-income patients and patients of color who are disproportionately impacted by medical debt lawsuits.

Advocates in New Mexico refuted claims that hospitals’ financial assistance policies were already sufficient by using hospital data which showed that a significant number of bad debt accounts were from patients who should have qualified for free or reduced care. They emphasize the need for more equitable and transparent hospital billing policies.

In Oregon, advocates developed a clever strategy pointing to the mission statements of each hospital and highlighting the frequent misalignment between a hospital’s community benefit expenditures and debt collection activities, and its stated mission of improving the health and wellbeing of its community members. Both Oregon and New York advocates also utilized an earned media strategy, leveraging coverage of hospitals’ aggressive collection actions to build support for the issue and increase public pressure.

Lessons learned from advocates in Maryland, New Mexico, New York, and Oregon point to the efficacy of empowered community members, using data to garner support and address the opposition, and building strong coalitions including grassroots organizing groups, immigrant organizations, health care providers and legal advocates. Employing these strategies through a racial justice and health equity lens is critical to ensuring that policies are driven by those most affected by medical debt and advance economic stability for all communities.