Whether it’s covering certain types of benefits, paying health care providers in certain ways or asking Medicaid enrollees certain questions, there are many ways in which the Medicaid program can address the “health-related social needs” of its enrollees, defined as health-harming conditions affecting individuals. As we’ve blogged about previously, the new year and new policymakers at both the federal and state level present opportunities for health care stakeholders to discuss and strategize about ways to address these needs, as well as broader “social determinants of health” (SDoH), defined as the underlying social, environmental and economic conditions affecting communities or populations. Since SDoH have been shown to have the largest influence on individual health, allowing for Medicaid to pay for health, not just health care, will be an effective way to improve the health and well-being of its enrollees.

Several states are in the beginning stages of allowing their Medicaid program to deliver care to patients in ways that address their health-related social needs:

North Carolina

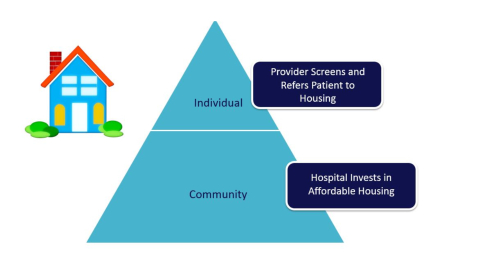

In October 2018, North Carolina received approval to require Medicaid managed care plans to provide a questionnaire, also known as a “screening tool,” to enrollees with high physical, behavioral or social needs that asks about four social determinants of health: housing, transportation, food insecurity and interpersonal safety/toxic stress. If enrollees identify having health-related social needs under one of these categories, health plans will then be required to make referrals to community-based organizations that will be responsible for delivering and coordinating health and social services to address these needs.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts is already requiring its providers to screen for health-related social needs, and is encouraging them to provide referrals to community-based organizations that can help address these needs. The state Medicaid program is now increasing payments to providers who care for populations that have health-related social needs such as unstable housing or “neighborhood stress.” “Neighborhood stress” is defined as residing in a zip code that has a high percentage of: 1) individuals and families who are living below 100 percent of the poverty level, receiving public assistance, or living without a car, 2) unemployed adults, and 3) adults age 25 or older without a high school diploma.

As these initiatives get off the ground, health care advocates have been tracking their development closely and providing feedback to states to make improvements, such as tracking the outcomes of the referrals to make sure they’re successful. While the health care advocacy community is excited by these new developments, we firmly believe that Medicaid funding shouldn’t be cut in other ways to pay for these types of investments. Nor should it be tasked with addressing broader social determinants of health that other public sector programs are intended and better positioned to address. Rather, we believe initiatives such as screening and referring enrollees for health-related social needs toe the line of addressing social determinants without stepping over it. For more information on how Medicaid programs can screen for health-related social needs, including other state examples, check out Community Catalyst’s new report on Screening for Social Needs.

Since Medicaid covers more than 70 million individuals, many of whom tend to be disproportionately affected by social determinants of health, the program can make great strides towards improving the health and well-being of its enrollees by identifying their health-related social needs, and working to address them. By allowing health plans to screen for whether or how enrollees are affected by social determinants of health and refer them to organizations that can provide services to address their needs, Medicaid can truly begin to look at the upstream factors affecting overall health.